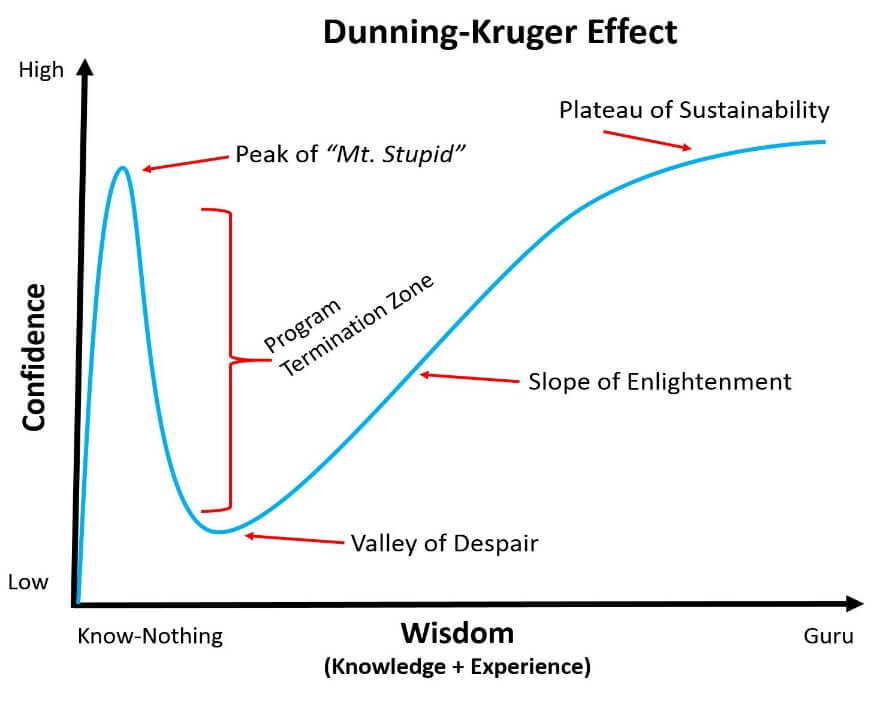

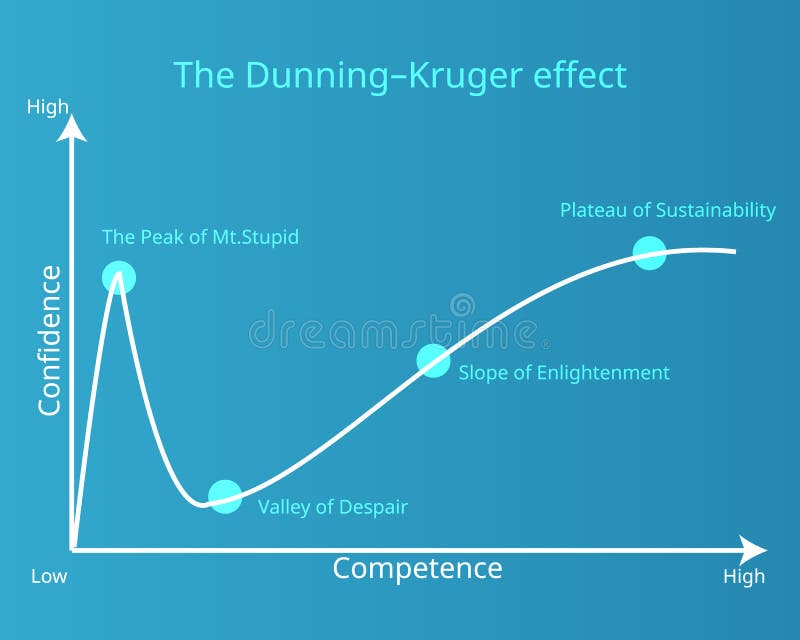

Meanwhile, scores in the center two quartiles are farther from the endpoints and, assuming random errors both above and below the accurate score, we would expect those means to move less. At the extremes, random error will bump up against the 0 and 100 endpoints of the scale, causing the quartiles averages to move toward the center (see the left panel of Figure 2). This was a quite reasonable hypothesis because random error added to the blue actual score diagonal of Figure 1 would tend to flatten the line. One of the first challenges to the DK effect was that it was just noise, meaning random errors of measurement. A graph drawn by the author showing a classic Dunning-Kruger effect outcome. This kind of finding has been replicated many times by researchers in different laboratories with tests on a variety of subjects.įigure 1. Conversely, the people who scored in the top quartile slightly underestimated their performance. People who scored low relative to other people greatly overestimated how well they did. The classic finding is shown in Figure 1, a hypothetical graph that I created on my computer. In presenting the results, Kruger and Dunning grouped the participants into quartiles (e.g., lowest 25 percent of scorers, next 25 percent of scorers, etc.). After completing the test, each student was asked to rate their performance relative to others on a percentile scale and also to predict the number of items they got correct. In Study 2 of Kruger and Dunning’s original article (Kruger and Dunning 1999), the authors gave college students a twenty-item test of logical reasoning with questions drawn from the Law School Admissions Test. The objections to the DK effect can get quite technical, but I will do my best to keep it simple. This is only proper and part of the usual scientific enterprise, but in this case, some authors came to the conclusion that what Dunning and Kruger had seen was just a statistical artifact of the process of measuring people’s performance and expectations. According to Dunning and Kruger, people who are ill informed often don’t know it.īut not long after the DK effect was identified, it was challenged. People who were unskilled or unschooled in a subject also suffered from a “metacognitive deficit.” Metacognition is thinking about your own thought processes, and it is separate from the basic thinking you do while solving a problem or taking a test. In a world where the views of experts are regularly dismissed (Nichols 2017) and many internet users think they know more about medicine and foreign policy than people who actually studied those subjects in school, the DK effect seems to explain a lot.

If you suffer from the DK effect, you know very little about a subject-which is bad enough-but you also have the false impression that you know considerably more than you do. Frequently applied in a political context, the Dunning-Kruger (DK) effect has rapidly become a famous psychological concept. It does not store any personal data.Ignorant of your own ignorance. The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary".

The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". These cookies ensure basic functionalities and security features of the website, anonymously. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)